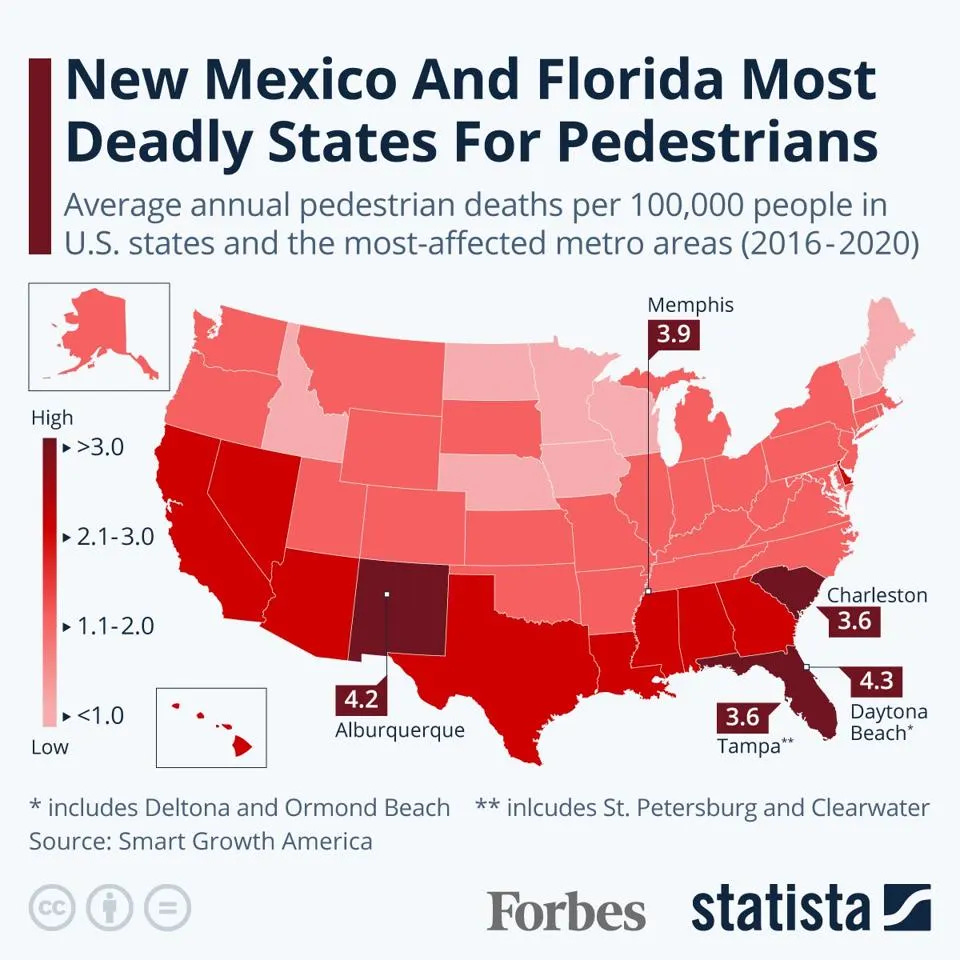

SC Is One of the Deadliest States for Pedestrians, but We Can Do Better

How Spartanburg County's Safety Action Plan can provide a path forward

This past week, Spartanburg County posted an opportunity to have our voices heard regarding road safety. One of the things about this call to action that stuck out to me is that it was geared towards all road users, not just those in cars. The survey provided includes questions for those who walk, bike, or use a mobility device to get around. In the United States, we have been inundated with the idea that the sole purpose of a road is to get cars to their destination as quickly as possible. This has resulted in road design and policies that create an actively aggressive environment for pedestrians and cyclists. South Carolina is one of the states that has paid the highest toll for this approach.

Wider trends have even shown that pedestrian deaths have been going up across the board since 2009. This topic was actually the subject of a recent episode of New York Times’s The Daily podcast. The podcast points to smartphone usage, the popularity of automatic transmissions versus manual ones, and the American trend of larger and larger vehicles as possible factors. There are obviously several different issues that are putting people at risk regardless of how they choose to travel.

The county post states that in the past five years Spartanburg County has had more than 50,000 crashes, 1,000 of which resulted in serious injury or death. When pedestrians die or are injured, most of the time it is due to inadequate infrastructure. This can mean the area lacks sidewalks entirely, or maybe those sidewalks are too cracked to be usable. I have experienced first hand plenty of sidewalks that are cracked and sloped, which would make them entirely impractical for a wheelchair user. Crosswalks are often not well lit, and most of us who are out walking may not have a fluorescent safety vest on hand. We should not have to. The crosswalks should be safer. Infrastructure should sufficiently protect folks.

For cyclists, they often have nowhere to bike. I own a bike but it is not what I use to get downtown, because the infrastructure between my two destinations just is not safe. Biking on the sidewalk is often looked down upon, but biking on the road without a designated bike lane is often an extremely uncomfortable and unsafe experience. When we do have bike lanes, they are all too often mere paint on the road. This often results in painted bike lanes being used for parking by cars or even as a glorified turning lane. Spartanburg’s very own Hub City Hopper has the designation of being the very first fully protected bike lane in the state of South Carolina, featuring a raised concrete barrier rather than just paint.

Who is affected the most

Of course people in our state often do not choose to walk or bike to places if this is the state of our infrastructure. These gaps are most prominent in low income neighborhoods and neighborhoods historically inhabited by people of color. The Forbes article states the following: “In the time frame of the study, an average of 4.2 in every 100,000 Native Americans and 3.0 in every 100,000 Black Americans died in such a way every year. In comparison, the average annual death rate in the country was just 1.9 in 100,000 during these years.” The Daily also finds that fatality hotspots tend to be places with lower rates of car ownership. Poorer, more vulnerable folks are most hurt by our poor infrastructure.

These are areas around our cities that are least likely to be given much investment. They are also communities more likely to live next to our most dangerous roadways. In the era of urban renewal these areas were viewed as blight that were often cut into pieces or completely erased by constructing massive freeways. There are still communities cursed by the legacy of urban renewal to this very day, even in our own city. South of Main by Beatrice Hill and Brenda Lee tells the story of how urban renewal affected Spartanburg’s southside. The way systemic racism has resulted in a lack of walkability is a blog post of its own that I will get to in due time.

Regardless, these do not have to be the outcomes of our built environment.

What can we do

First off, we need to recognize that this is not normal. Feeling the need to tell someone to drive safe is not normal. Having a traffic death in front of a high school at least once a semester is not normal. Drivers treating city roads like NASCAR tracks, putting someone else’s life in danger to save themselves fifteen seconds of their commute time, is not normal. Victim blaming pedestrians and cyclists for dying in a world purposely built to make their lives harder is not normal. We need to realize that we have the capacity to do better.

I have recently joined Spartanburg’s local Citizens for Safe Streets initiative, because I do think that change starts with us. It starts with serious conversations about what we allow to happen on our roads. It starts with a refusal to regard this immense bloodshed as normal.

We can also advocate for streets that are built better. Part of the reason why American drivers are so dangerous is that we build roads that incentivize that behavior. It has been shown that building more lanes does not fix traffic. If more lanes fixed traffic, then the 8-12 lane monstrosities found around Atlanta and Los Angeles would not be at a constant standstill. More lanes often create more traffic due to the idea of induced demand, meaning that creating more of something simply results in increased usage of that thing. These roads feel efficient when they hit their peak times, but when the lanes are empty they just result in an environment that gives folks permission to drive faster. Driving faster can make it more difficult to react when faced with a variable such as an elderly person with a walker crossing the street or a kid on a bicycle.

Once a road is more than four lanes, it leads to diminishing returns. It should not be controversial to say that a city street should not be built to function like a highway. There are many roadways in Spartanburg that would be safer if the lanes were cut down and replaced with bike lanes, safer walkways, and more ADA accessible crosswalks. Making alternate modes of transportation safer and more comfortable would likely lead to more people choosing to get around that way, lessening vehicular traffic.

These changes in design are traffic calming measures that result in safer streets for all users. Rather than focusing on getting someone from point A to point B as quick as possible, we need to make transportation more equitable and safe. Drivers pay more attention when they know they have other users to account for. When streets are narrower, they are more aware of the speed they are going. Even the presence of trees in a median can help to calm traffic. We can redesign our streets based upon this standard.

The final call to action I will include is the survey link posted by Spartanburg County, which you can access here. This is just one of many ways that you can have your voice heard regarding these issues. Be sure to have conversations with neighbors, reach out to Citizens for Safe Streets, attend city council meetings, call your county representatives, and even share this blog with others. Together we can ensure that our roads are built with safety and equitable transportation in mind.

Until next time,

Liv.

Great post. Thanks for all this information and for bringing these issues to people's attention. I love walking, but I often feel unsafe walking in our community. I highlighted my concerns as a pedestrian and a driver in my response to the survey.